Secrets of the Oak Woodlands: Plants and Animals among California’s Oaks

Excerpts from the California buckeye chapter

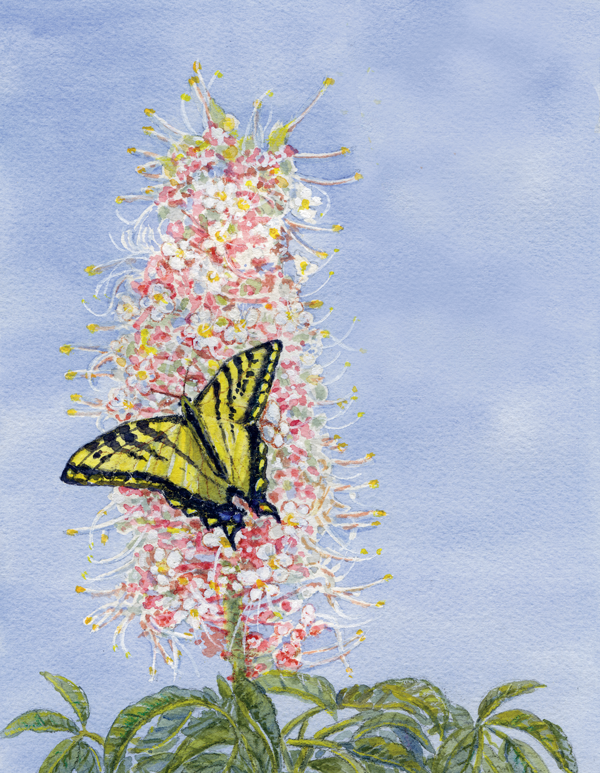

“California buckeyes unfurl their soft, many-fingered leaves in late winter and early spring, bringing luminous green cheer to landscapes still clad in somber grays. In May and June they again brighten our hillsides and canyons by transforming into giant flower candelabras, and in fall their seeds—the largest produced by any California native plant—droop like exotic testicular ornaments from bare silvery branches. The seed husks later crack open, allowing glossy brown “bucks’ eyes” to peek out between thick greenish lids. In winter, sculptural trunks adorned with moss and colorful lichens curve skyward while festoons of light green lace lichen dangle from the trees’ upper reaches.” (p. 21)

“By producing large, five- to seven-fingered leaves as early as February, buckeyes get a head start on the growing season, gathering sunlight before the rainy season ends and before other trees leaf out and engulf them in shade. While other trees are still dreaming of spring, buckeyes’ leaves are already in high gear, photosynthesizing the sugars necessary for the growth of trunks, branches, flowers, seeds, and leaf buds. In a stroke of evolutionary genius, the leaves of this “summer deciduous” species start turning yellow when the trees begin to go dormant, often as early as July, sidestepping the problem of water loss during the driest months. When water is plentiful they keep their leaves into fall. (p. 22)

If you have a chance to look at buckeye flowers with close-focusing binoculars, you will enter a microcosmic world impossible to imagine from what you can see with the naked eye. In addition to close-up views of butterflies, you will see highly magnified beetles, flies, and native bees, all with their own interesting shapes and sheens, quietly gathering nectar/or and pollen. Because they have coevolved with the California buckeye for countless millennia, native insects have acquired resistance to its toxins.” (p. 23)